Is it possible that we’re influenced by recent events a little too much?

Ever since I began my journey in sports journalism, I’ve wrestled with the idea of whether I, and the wider sports industry for that matter, should focus on covering the most recent and upcoming stories, or take more to time to produce more sound and well-founded content. And while I have opted for the latter, it seems as though the sports industry has no intention of jumping off the ‘recent trends’ train – and I think that creates a big issue for the integrity of the industry on the whole.

When we cover and engage with sports, we are often most interested in, and give the greatest respect to the things that have happened most recently. For some it’s the most recent games and performances by teams or players; and for others it’s the most recent or viral stories and segments from the most heralded sports journalists and pundits.

But with that interest in the most recent events, comes a relative disregard for the past. It may be previous performances by those teams and players or older stories from those same elite journalists – these historical elements of sports coverage are pushed right to the back of our minds. It might be because we’re bored of what we already know, or maybe we don’t want to get left behind in an industry that is racing to write the next hit piece. Regardless of why, we clearly have a greater affinity for the newest news, narratives, and events.

The sports industry seems to have become an industry of reactors as opposed to analysers and trendsetters.

But the issue doesn’t lie in what we enjoy to talk about or what we leave in the backs of our minds. The issue is with how those very actions influence the wider coverage of sports. We may be uber-interested in the most recent performance from a specific player or team, but that performance is just one of many in a wider body of work that that player or team has produced. So, when we cover sports, we may be most interested in what that player or team has just done, but we ought not to lose sight of the fact that it is just a fraction of the bigger picture.

And the issue is that we don’t do that. Our infatuation with the most recent events lead us to place a disproportionate stock in those recent events. And by leaving old news in the backs of our minds, we lose sight of the fact that those older events should carry just as much weight in the wider body of work as recent events do.

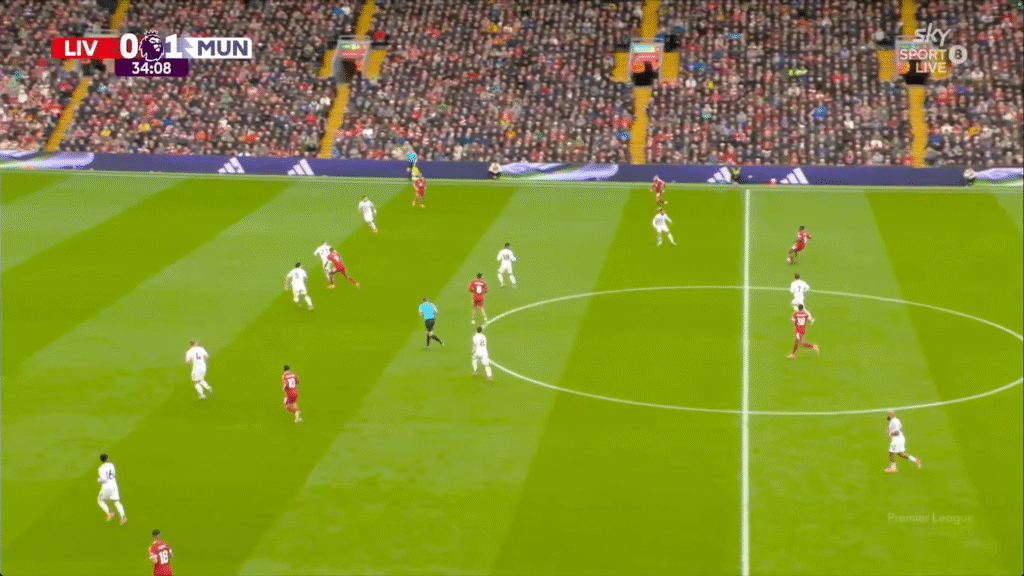

And this leads to the main argument of this piece. Our ideas and coverage of sport is influenced by something called recency bias. A cognitive bias where people place too much emphasis on recent events or the latest information when making decisions or forming opinions, often ignoring more relevant historical data or long-term trends. So, when I saw Ibrahima Konate play this pass (below) through three lines of defense against Manchester United, I formed the opinion that his progressive play had improved a lot, and he was capable of repeating such play in future games.

And, in the same way, when he was targeted in possession against Manchester City just a couple weeks later, a lot of people were quick to label Konate as ‘terrible on the ball’. In both cases, opinions and statements were influenced by recency bias. I didn’t give the proper weight to Konate’s struggles on the ball over the last couple seasons and opted to put great stock in that one game against Manchester United. And on the other hand, a lot of football fans placed a lot of stock in that game against Manchester City, and disregarded the strides that Konate has made in that aspect of his game.

And although this is just one example of one player and just a couple games, you can find many similar instances of recency bias having a major influence over the leading ideas and narratives in sports. Just last night, Willian Estevao convincingly outplayed Lamine Yamal in Chelsea’s 3-0 domination of Barcelona, and that his prompted some to both overrate and underrate each player respectively.

Or to show that this isn’t just unique to football, Matthew Stafford has experienced a wild and tremendous reputation change since being traded from the Detroit Lions to the Los Angeles Rams in 2021. As a Lion, Stafford was seen as a slightly above average QB that was a perennial loser. In fact, a 2015 article from The Guardian that called him ‘a $53 million mistake’ and accused him of ‘wasting his access to a strong defense and one of the game’s great receivers’. And while that is a harsh reputation to give someone, it wasn’t completely baseless. He won just 45% of his games as a Lion (74-90-1) and threw just 2 TDs for every INT (282-144). He was good, but not great.

Since joining the Rams, however, Stafford has become a consensus top-10 QB in the NFL and even won a Super Bowl in his very first season, quelling the ideas that he was just a loser with a big arm. In LA he has won 63% of his games (43-25) and has thrown 125 TDs to 45 INTs (2.8:1 TD-INT ratio). He’s been better, but it could be argued that he’s pretty much the same player, just in a better situation.

Nonetheless, silencing the idea that he was a perennial loser has done wonders for his reputation, and completely changed the way that his days in Detroit are being recalled. Instead of the Detroit days being an indictment of Stafford and the organisation, they have become purely one of the Lions front office. And while it may be fair to say that Stafford wasn’t given the conditions to really show his talent and ability to win, it doesn’t make sense that our most recent experiences watching Stafford should change how we remember the past. He is now being touted as one of the best QBs of all time by some commentators.

In fact, the popular podcast Speakeasy argued that Stafford will be ‘top-6 of all time if he wins another Super Bowl’. Now I have no problem with these kinds of takes being made, but I am concerned with how drastically recent events seem to have on the way we remember history.

For a player to go from a $53 million mistake to better than all-time greats like Peyton Manning, Aaron Rodgers, and Drew Brees is a very sharp pivot when you consider that there are only 4 and a half seasons in LA that have caused this reputation shift. And his 2022-24 seasons were not the most impressive either. A lot of the heavy lifting is being done by the Super Bowl winning year in ’21 and his MVP caliber season so far in ’25. The power of recency bias has dictated that two elite years are enough to erase the kind of reputation that at one point seemed unshakable.

But from this, come two important questions: why does recency bias have a tangible effect on sports coverage? And, if recency bias does have an influence over sports coverage, what does this mean? After answering these two questions, it will be clear that recency has a major influence over the way sports is covered, and that very influence has a negative impact on the integrity of many takes, articles, and reports in the industry.

To tackle the first, it’s important to understand why biases are powerful, but more importantly: the motivations behind the sports media industry.

Biases are powerful because, for the most part, we don’t know we’re being influenced by them. These are known as implicit biases – those that happen subconsicously and often so quickly that we dont even know that they’ve taken control of us. When Emmanuel Ocho and LeSean McCoy argued that Stafford has always been this good on Speakeasy, they weren’t making that assertion with the idea that his recent success, especially this season, is influencing their idea of his time in Detroit – they think they’re being rational by using the recent information to inform something about the past. And that’s why biases are super dangerous – even when we think we’re being reasonable and rational about something, we may be under the influence of a bias that we simply can’t detect.

But more importantly, the influence of recency bias is fantastic for helping the sports industry achieve its goals. In modern times, businesses are competing for people’s time. Clicks, likes, reposts – these are all primary goals for creators in the sports industry. And more than anyone else, the casual or new fan will be most susceptible to recency bias as they don’t have the knowledge or care to understand how a recent event fits into the wider narrative.

So, when those on the Speakeasy podcast make that claim about Stafford potentially being a top-6 QB in the all-time rankings, it provokes responses from fellow fans that are also influenced by that recency bias. Some will like it, some will share to their friends, and some will repost it to further the narrative. In any case, the sports industry wins and profits from the influence of recency bias.

Essentially, since everyone is influenced by recency bias, to some degree, the sports industry playing into that, to generate engagement from fans ends up being a net positive for the space. Even though those in the industry have the expertise and knowhow to discern whether a recent spike or dip in performance should influence the wider narrative, it simply doesn’t make sense for them to do reasonable analyses that most people won’t relate to.

And it explains why these provocative takes are so widespread; and long-form, deep dives are less popular. The average fan doesn’t relate to it and thus won’t engage with it.

It’s why personalities like Stephen A. Smith and Skip Bayless have held prominent positions in the industry for almost 2 decades. It isn’t to say that they don’t know ball, because they absolutely do, they just know that spewing all of their knowledge of the game isn’t what will get people to tune into their shows.

In fact, that approach was the one JJ Redick primarily used when he was on First Take, and it left him largely frustrated. He once said that people don’t truly appreciate the game of basketball and all of its nuances in one of his appearances on the show. They love highlights, headlines, and emotional responses. And he’s right, most people tune into sports shows for the entertainment and not the thorough breakdowns.

Ironically, it doesn’t make sense for the sports industry to be littered with experts using their expertise; it is more beneficial for those leading figures to be more provocative, emotional and influenced by recent events.

But what I will say is that for all the reasoning vs emotion when we say Redick debating Stephen A., is that there does seem to be an audience that appreciates that slow and rational analysis that Redick brought as he has been one of the most popular personalities on First Take. There are many viral compilations of Redick ‘owning’ his peers on First Take, which highlight his sound arguments and the use of long-term stats and trends that support those arguments.

Trying to understand why this happens is where the philosophy of sports fans can be examined. You might think that sports fans would want to learn as much as they can from those who know a lot about a given sport, the same way you might assume that someone would like to know what the right thing to do is in a moral dilemma. In both cases however, people are most comfortable when they can find evidence that confirms their initial ideas or intuitions.

This idea forms part of Jonathan Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model (SIM), where people form opinions based on their intuitions, and then look for evidence that backs that up afterwards. With sports, this would be like seeing Matthew Stafford play tremendously this season and form the opinion that he’s an all-time great QB. Then looking to his time in Detroit and saying that the organisational blunders were the reason he didn’t reach these kinds of heights, and thus, he has always been an elite QB. Here, the influence of recency bias has a direct impact on the way evidence is collected, and the past is remembered. So, while it may not be a rational way to make arguments, it is a comfortable one and many would rather do that than truly challenge themselves on their own ideas. This is exacerbated when fans see this kind of argument composition being done by those who are meant to be ‘experts’ in the industry like Stephen A. Smith and Skip Bayless.

So, it’s clear that due to the way people form beliefs and are drawn to information that supports their beliefs and ideas, recency bias does have a tangible effect on the way sports are covered. Now to tackle the second key question: what does the influence of recency bias mean for the sports industry?

Since a bias is a tendency or inclination to favour one side, person, or thing over another, often in a way that is considered unfair, closed-minded, or prejudicial – sports coverage being influenced by it is a problem. As reporters, pundits, and fans, we ought to be fair in the way that we form opinions and share stories. But as I’ve already covered, that isn’t the case due to the influence of recency bias.

This means that any given article that you read or video that you watch may be unfairly using recent evidence or disregarding historical events to make its arguments. This is obviously an issue for an industry that aims to provide a gateway for the average fan into understanding what has happened in sports and the way those sports work. The famous saying ‘don’t believe everything you see online’ could be extended to those who produce content in the sports industry if short-form, engagement driven content continues to be the focus.

More alarmingly, the integrity of the industry can be called into question and that can have catastrophic consequences.

If the influence of recency bias in the industry was better understood and scrutinised, there is a world in which people begin to lose trust in those that contribute to it. If people begin to catch on to the idea that the influence that recent events have over wider narratives is disproportionate to their true weight in a wider debate, there is a good chance that people become extremely skeptical about the vast majority of sports coverage.

That is a problem. The reason the sports industry works so well is because we, as consumers, have trust and faith in the integrity of the content that we’re being exposed to. If that faith dwindles, the industry will find itself in a world of hurt. And while it may seem like a world in which we are skeptical about sports media is far away, this article acts as evidence that it isn’t that far fetched an idea. If I can see how recency bias is impacting sports coverage, then I’m sure I’m not the only one, and it clearly isn’t impossible for others to follow suit.

What can we do to solve this then?

Well, the sports industry is littered with ex pros, scouts, and brilliant minds – there is no reason why they cannot tap into that expertise and reduce the emphasis placed on the most recent events. They have the expertise it takes to properly discern how impactful a recent event should be on a wider narrative. So, the problem is not with those that currently make up the industry.

If viral clips and wild headlines were swapped for more deep dives and informed debates, we would likely see the power of recency bias dwindle and thus the integrity of the content would be stronger. It may result in sports media company experiencing less growth, fewer views, and a fall of in engagements, but it would solve the issues that recency bias present.

It may seem like I’m oversimplifying the solution to a fairly large problem but that is because I argue that the solution is really that simple.

If we’re liable to be influenced by a bias that preys on the recency of events, then we can make a concerted effort to stop producing content that revolves completely around those events in isolation. Instead of pieces being written solely about the latest games and events, maybe we can feed them into their respective wider narrative(s) or circumstance(s) surrounding that player or team. That way, we have a better chance of truly capturing the true weight of recent events as we’re placing them into a wider and more full context.

And whilst a lot of this article have been in reference to my and many others’ personal experiences with sports coverage, this solution is grounded in academic work. A paper on recency bias by ScienceDirect stated that,

‘The recency effect is increased when too much information is presented too quickly, and it is reduced when coupled with other tasks.’

This reinforces the idea that quick-fire, short-form content, that consumers can watch a lot of in a short amount of time, exacerbates the issue. And also that if we couple our coverage of the latest events with other tasks like setting out a wider narrative, doing deep dives, or answering long-term questions, we can reduce the effect of recency bias in the world of sports coverage.

Why it likely won’t be solved though…

These solutions assume that the industry is predisposed to having a primary goal of producing strong, informed content; and it isn’t totally clear that that is the case.

Fundamentally, TV stations, newspapers, and social media channels want to grow, and recency bias is actually good for them as they can capture an audience that is also affected by and responsive to those same biases.

And since most sports fans aren’t looking at historical trends and data when deciding just how much stock they should place in the most recent events, content that utilises those trends and data won’t be relatable. Thus, the content won’t generate engagements and subsequently won’t foster the kind of growth that these companies are fundamentally chasing.

Even though an emphasis on the expertise and reasonable analysis of industry experts would improve the quality of content – it isn’t clear that this emphasis would lead to growth and engagements. Thus, it isn’t of much use to the industry (as currently constructed).

To conclude, recency bias is a problem. It directly influences the coverage of sports; it places disproportionate weight on the most recent events; and even has the power to change the way we remember the past. In a vacuum, recency bias is not good. But to an industry searching for ways to better engage its audience – it is the perfect ingredient and it likely will be for years to come.

Are Liverpool trying to be like the Dodgers?